Downside Protection Methods

Downside Protection is when you own two or more assets that are negatively correlated to each other, so that when one goes up in value the other will go down. It's also known as a 'hedge', and is often implemented with options.

Types Of Downside Protection

If you own shares of a stock (i.e. you are 'long'), the ways you can achieve downside protection include:

- using a stop order

- buying an inversely related security

- shorting a directly related security

- buying puts

- selling calls

It's rare that a hedge will be so perfectly correlated to the initial investment that it's a zero-sum result (meaning, you make exactly as much on the hedge as you lose on the initial investment). And if it is perfectly correlated then you've removed any upside potential from your initial investment.

Let's take a look at each of these techniques.

Downside Protection Via Stop Order

Some investors like this strategy because it is simple to execute and doesn't cost anything. You just place a good-til-canceled stop order with your broker and forget about it. If the stock ever trades below your stop level then your broker will generate a market order to sell your shares.

Although simple and low-cost (free), it's not perfect. The biggest complaint is that stop orders do not protect you from gaps down. For example, if you had a $100 stock and place a $90 stop order, and then after hours the company releases poor earnings, and the stock opens at $80 the next morning, then you will receive around $80/share for your stock. That's a long way from the $90 stop you placed. But that's the nature of stop orders...you are not protected from large downward moves outside of normal market hours.

Another issue with stop orders is that your stock may only briefly drop below your stop price (causing you to sell it) only then to recover and head upward. Stop orders can be gamed by other traders, especially if you place them near round number prices where many other investors typically place them.

Downside Protection By Buying An Inversely Related Security

This can be effective, especially if the two securities are closely, but inversely, related. It can also be a good technique when you want to avoid selling your long position (for tax or other reasons). For example, if you are long SPY you could buy SH (ProShares Short S&P 500 ETF). As SPY goes down, SH will go up.

It's harder to use this strategy with single stocks because there aren't many pairs of stocks that trade directly inverse to each other. Sometimes competitors in a tight market will trade inversely since one's gain is often the other's loss, but this is hard to find on a per-company basis.

Downside Protection By Shorting A Directly Related Security

This is similar to buying an inversely related security, and has the same problem in that it's difficult to find company pairs that move directly with each other (plus, not all accounts are approved for shorting). However, sometimes you can find securities that are close. For example, if you are long SPY, you could short DIA or IWM.

Downside Protection By Buying Puts

This is the classic way to get protection. You buy a put option on the same security that you are long, knowing that you are 100% protected from the strike price on down. At any time before the expiration day you can 'put' your shares to the person who sold you the option and receive cash per share equal to the strike price (even if the stock has gone to zero). That's how puts work.

It's popular because it's bullet-proof downside protection, and it also allows for continued upside potential should the stock rise. The problem is that it's expensive, especially on volatile securities. People refer to put options as 'insurance' and like most insurance, it can sometimes be too expensive to insure 100%.

Downside Protection By Selling Calls

For many investors, a happy balance between cost-of-protection and amount-of-protection lies with selling calls against their long positions, often times even selling deep in-the-money covered calls. This technique does not provide the same level of insurance as buying a put but it is also a whole lot less expensive.

For example, let's say you own a stock trading at $100. You think the next couple of months could be rocky so you sell a 2-month call with a strike of $90 for $15. That means that (1) you receive $15/share in cash today, and (2) in 2 months time you will either lose your stock at $90 (plus the $15 you got today, for a total of $105/share), buy back the call options (and perhaps sell others), or keep your stock and have the options expire worthless (if the stock is below $90 on option expiration day).

This is the classic in-the-money covered call trade. You earn some time premium ($5/share over 2 months in the above example) while enjoying some downside protection ($15 worth for 2 months, meaning the stock could drop from $100 to $85 during the 2 months and you'd come out even... the $15 loss on the stock is offset by the $15 in premium you received for the option). The downside is that you have capped your upside (you won't benefit if the stock rises over $100 during the $2 months). But for many people, capping their upside is a reasonable trade-off to get 15% downside protection for 2 months. (Note: if the stock drops more than 15% then you will lose, but the first 15% of any drop from $100/share is covered by the $15/share option premium you received.)

Max Protection

Born To Sell offers a special screening tool for investors who want to define their annualized return goal, and then see candidate trades that have the most downside protection. To use it, first go to the Max Protection sub-menu in the Search tab:

Next, set the Minimum Annualized Return to your desired annualized return. For example, if you want 1%/month that would be 12% when annualized so you'd set the slider to 12%:

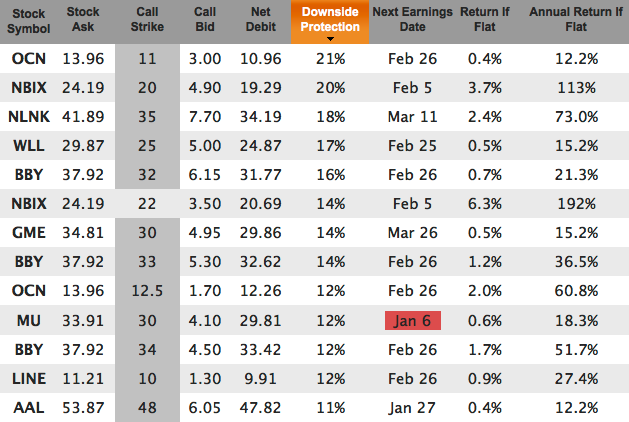

Then set the Expiration slider to your time horizon (Jan 17 in this example) and the Stock Price slider to the min and max stock prices you are looking for. The results are sorted by Downside Protection, with every covered call on the page having an annualized return that is greater than or equal to the minimum value you set. The items at the top of the list have the most downside protection:

As an example on how to read these results, let's look at NLNK (the 3rd row). You could buy the stock for 41.89 and then sell a 35-strike call option with an expiration date of Jan 17 for 7.70. Your net debit (out of pocket cash) for today would be 34.19 (41.89 - 7.70). That's your break even point.

The downside protection is 18%, meaning NLNK could drop 18% from its current $41.89/share before you'd start to lose money.

If NLNK closes exactly at 34.19 on Jan 16 (day before expiration) then you break even on this trade (don't make anything, but also don't lose anything). If NLNK is 35 (strike price) or higher on Jan 16 then you make a 73% annualized return (you will receive $35/share for your stock on Jan 17, after having paid $34.19 for it today).

Note: One thing you do not want to do is blindly use search results (from any software, not just ours) as a bunch of trades to go execute. You need to know why these stocks are offering these kinds of premiums, and that requires homework on your part (for example, NLNK is involved in looking for an Ebola cure right now, and is volatile based on if those tests show progress or not). But the Max Protection feature is a time saver when looking for a place to begin your research for deep in the money covered calls that offer the most downside protection given your annualized return goals.

Mike Scanlin is the founder of Born To Sell and has been writing covered calls for a long time.